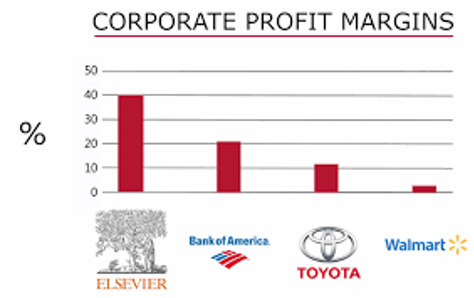

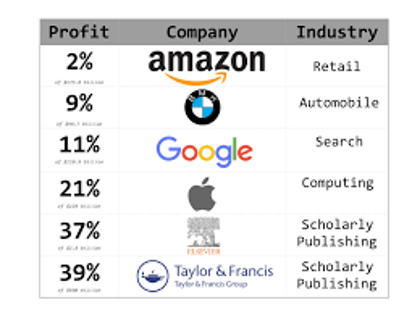

Over the last few years, similar to news media, a lot of ink has been spilled over perceived market failures in academic publishing. In a stark contrast with news media outlets however, science publishers are booming, with operating margins in the industry being some of the highest of any industry globally. These are achieved despite most of the output being found to be inaccurate when independent researchers attempt to replicate it.

The reason they command such high profits for a poor product is because a perverse economic model has become entrenched in the industry. The model is one in which the public funds scientific research, which is then published in journals without any payment in return. The journals then, quite incredibly, charge publicly funded universities for access to the content. In sum, governments must buy the product they themselves paid to be produced. Governments are slowly waking up to the situation, but their room for manoeuvre is minimal on account of property rights laws.

The Creation of a Coordination Problem

How does such an incredibly bad system come into existence? How does it persist? The answer to the first question is that entrepreneurs were able to exploit three realities of the industry in the pre-internet era. Firstly, before the internet democratised publishing, it was a highly specialised activity that required quite a bit of know-how. Secondly, since publication was the sole method via which scientists could share their work and enhance their career prospects, this granted those with the know-how to publish, great market power – the journals became the kingmakers in science. Thirdly, the only customer of note is the government, an enormous institution, whose spending can be conducted through numerous independent bodies, none of which are subject to market discipline, that ascertaining whether the money is well-spent or not can be extremely difficult. The system persists because copyright laws have entrenched or locked this exploitation in with seemingly few ways out despite a belated realisation that the spending represents almost the worst value for money one could imagine in the internet era.

When governments embarked on a big push to industrialise science in the post-war years, the free-to-read journals that scientific societies published struggled to keep up with the increased output of content. They, after all, were not businesses optimised to profit from publishing, but organisations that relied on support from government and various NGOs to run their printing operations. Unsurprisingly they were not very efficient at the task. This situation naturally created an opportunity for those that were. Several companies, most notably Pergamon owned by Robert Maxwell (the infamous Ghislaine Maxwell’s Father), and Elsevier took notice. Of course, businesses can only exploit the opportunity if it is a market opportunity, and it cannot be a market opportunity if there is no expectation of profit. There can’t be an expectation of profit in the information business unless a) businesses can charge for it and b) they can prevent other people from copying the information and offering it for free. They set about implementing a strategy that not only achieved both of these goals, but achieved it with margins publishers in other information sectors could only dream of.

The key to the publishers’ success was that they realised the governments, who were in a race with each other to become centres for the pursuit of science through their rapidly expanding university systems, were for all intents and purposes, the sole consumer in the market through the public university system. As well as having large budgets, the spending decisions were made via numerous bodies that didn’t necessarily talk to each other. The final piece of the jigsaw was that the content produced for publication was part of this publicly funded system, and therefore its producers weren’t seeking a direct profit from the publication of the information itself. If was the increased notoriety that led to further career opportunities. The combination of these factors, along with the fact existing publishers couldn’t keep up with the increased supply of articles, conspired to enable the entrepreneurial market entrants to extract enormous rents from the market.

Pergamon and Elsevier were able to obtain a product from scientists and have them agree to sign over copyright without having to make any payment in return. Governments, knowing they needed these types of companies to get the research out, agreed to increase their budget for publishing to meet the higher prices they charged in return for satisfying supply. Since funding was dispersed to various bodies and various parts of universities who funded the scientists that produced the articles and the libraries that purchased the publications and these decisions were made independently, most people didn’t realise the primary investor in the system, the government, was essentially paying for the same product twice. If anyone did realise it, they likely assumed the cost of publication was worth it to grow the sector, without realising the beast they had unleashed. With the benefit of hindsight, since the government was both the investor and the primary consumer of this product, the publishing sector is one of those rare areas in the economy that should’ve been nationalised. The publishing element stood out as the only element that wasn’t nationalised.

So what beast had been released? Publishers were acutely aware that governments were actively seeking science publication to become prestigious. Thus, they knew the structure of the industry put them front and centre when it came to offering this prestige. It was they that gave the scientists’ work gravitas. It was publication on their platforms that offered a pathway to career advancement in this system. The publishers successfully fostered a ‘publish or perish’ culture where only work that appeared in their journals was paid attention to. Publishers know what makes people tick. Scientists, being human with egos like the rest of us, like the prestige. The publishers exploited this reality and systematically set about increasing the supply of prestige to as many scientists as they could. They created an endless number of journals to cater to the ever-increasing number of fields of study. The more they created, the more scientists that were published in them pushed their libraries to subscribe to them as there’s no prestige in work nobody reads. Critically, this system becomes further entrenched with each published article because if a scientist wants to learn from and cite the work of others in their field, they need to be able to read it. They can only read it if their university subscribes to it, and these push and pull pressures exerted on libraries represent the vicious circle that was created, and it exists to this day.

The more the system became entrenched, the more publishers increased their prices, knowing the position of power their ownership of copyright bestowed them with. Their costs however, remained negligible as they continued to produce their product with the assistance of free labour. Operating margins increased to over 40%, a figure unheard of in any other publishing sector. By the 1990s, faced with being pressured to sign up to a never-ending number of subscriptions, library budgets began to break. With internet adoption exploding right around the same time, many rationally thought this system would be disrupted.

This, quite famously, has not come to pass.The publishers responded to both the stretched librarians trying to keep up with steady flow of new journals and the possibility of increased competition from the internet dramatically lowering the cost and know-how required to publish by digitising and bundling their journal offerings into a single subscription. On the one hand this gave the appearance of lowering costs – the carrot – and on the other hammered home to librarians the bleak reality that a few companies ‘owned’ all the science their academics needed access to – the stick. By 2015 three companies controlled half of the market and the other 50% wasn’t particularly well distributed either. The bundled subscriptions have barely impacted profit margins despite the touted cost savings at their inception. It’s an oligopoly and if librarians refuse to buy these bundled offers, their academics would be frozen out of science. Thus, the combination of industry concentration and copyright rules enable the system to perpetuate when it would almost certainly otherwise be disrupted. This of course represents what looks like a very tricky…..

Coordination Problem

It’s a very costly perpetuation. As an example, the EU spends €450 million per annum on subscriptions to articles that were publicly funded either by its Member State governments or others. While the publishers take in billions in profits despite offering incredibly little value, the majority of the rent they extract comes from copyright for work they themselves didn’t produce. To make matters worse, the costs to society aren’t just felt in high prices, the product is hugely affected by the incentives that are inherent to this system. Since the onus is on scientists to be published, they are pressured to produce work that is ‘publishable’. Scientists know that the journals want something that is likely to grab other scientists’ attention and be cited. They know this because a metric known as ‘the impact factor’ that simply measures the number of citations a journal has, plays a big role in how institutions view a certain journal relative to its peers. Indeed, the number of citations an individual academic also has a huge bearing on their career prospects.

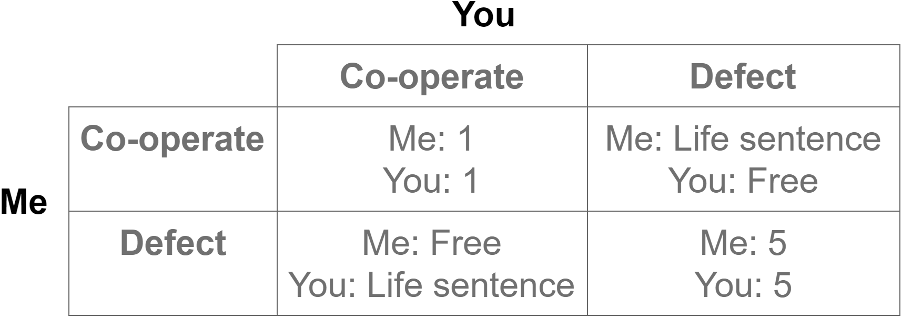

Academic publication thus has two quality control systems. One – peer review – imposed by the journals on their contributors, and the other – impact factor – imposed by academic institutions on the journals. It is only the first of these systems that interrogates the information submitted, however. The latter, somewhat inexplicably, is viewed as a proxy for quality. The reason this is inexplicable is that there are many incentives to cite articles for reasons other than quality and little incentive to cite an article purely because it is high quality as everyone relies solely on the impact factor once an article has passed peer review. However, since we know it is publication and citation that advances both careers in academia and the financial fortunes of journals, one doesn’t need to be an expert in game theory to reason that the impact factor will trump peer review when push comes to shove.

Apart from needing to satisfy the economic incentives of journals by producing positive, exciting findings, networks of academics are far more incentivised to cooperate with each other through reciprocal citation than to ignore work published by highly regarded peers they view to be substandard. The situation is exacerbated when one understands that peer review is both voluntary, unpaid work and conducted by academics that generally inhabit the very same networks the contributor does. Even if this weren’t the case, if one cites an article, to criticise it, which still does happen despite the incentives, this citation is treated as a mark of quality under this system.

The Externalities of a Coordination Problem

One of the many insightful quotes attributed to the recently deceased Charlie Munger is “show me the incentive, and I’ll show you the outcome”. I’ve just outlined a theory that the impact factor is both likely to be a poor metric for quality and to render peer review ineffective due to the incentives involved. Can I show you poor outcomes? The answer to that question is an emphatic yes. There is a well-known replication crisis in science. Around ten to fifteen years ago, some academics began putting the theory that the academic publishing system produces bad outcomes to the test. They began attempting to reproduce the results of articles by applying the very same methodology to the very same dataset the original scientists used. The results were shocking. Upwards of 80% and in some fields upwards of 90% of results failed to replicate. This was conclusive proof that peer review protocols were consistently missing serious errors. The primary reason for the crisis is a phenomenon known as p-hacking where data is manipulated, either consciously or unconsciously, to give the journals the exciting positive findings that are commercially desirable. The end result is that this field that is so revered by many across society is producing shockingly poor output.

Despite widespread acknowledgement of the problem, little has changed. Replication attempts continue to occur spontaneously, the results continue to be abysmal, however reforms aren’t forthcoming as it’s simply not in the economic interests of journals to start screening articles more heavily and those at the top of the academic pyramid also benefit immensely from the system. They certainly don’t want to see the articles that built their careers retracted. It’s therefore tantamount to career suicide for younger academics starting out to try to use parallel systems or even attempt to reform it from within, as their rung on the ladder will be taken by someone willing to play the game. Overall, the great tragedy is that most science that is being published is bad and lots of potentially very useful but ‘unexciting’ science is not being shared.

As with the case of news media, although for diametrically different reasons, we are faced with a problem the industry can’t currently solve. Can government solve it? They can certainly move the needle, but it appears only very slowly. Everyone knows the root cause of all the problems I’ve just written about is the unintended consequences of permitting the journals to own the copyright. Since science is international, the copyright is secured in multiple jurisdictions and recognised internationally via interstate treaties. The only way to reform the rules would be via a multinational agreement that severed the journals’ rights, something that is itself an enormous collective action problem and usually only happens for the very biggest problems humanity faces. See global tax rules, AML and climate change as examples. Given the unlikelihood of such cooperation, states are trying to incrementally solve the problem by unilaterally forcing academics to publish on platforms that don’t assume copyright and forcing journals to make new content open access in their jurisdictions. This amounts to embracing Plan S, an initiative by cOALition S. The journals have responded to these initiatives by charging scientists to publish on their platforms as they’ve no other way of making money.

So the government is still paying, the publication costs have just been shifted to the research budgets granted to academics instead of being allocated to the budgets of librarians. Not only does it not solve the bad economic deal governments are getting, it does nothing to remedy the incentives that are producing bad science. At the current rate of growth of open access journals, it will take decades, if ever, for the power journals have over science to be sufficiently diminished that the Overton window for greater reform will become wide enough. Over 75% of academic papers that have ever been published are behind paywalls. I, for one, given what’s at stake, think humanity should not have to wait that long.

When Collective Action Overcomes Coordination Problems

The verb ‘to boycott’ entered the English lexicon subsequent to a social protest movement against the abuse of property rights in Ireland in the 19th Century. It was the family name of Captain Charles Boycott, a 19th-century English land agent. In 1880, Captain Boycott managed an estate in County Mayo on behalf of a landlord who had inherited rather than earned the land and whose ancestors had been awarded the land by conquest. Exacerbating the sense of injustice, the landlord didn’t live in the country nor contribute to the local economy. He simply extracted a rent from his property rights. The newly formed Irish Land League began advocating for tenants to withhold rent and cease cooperation with these landowners that were demanding unaffordable rents. When Boycott tried to evict tenants who didn’t pay, the League organised a campaign against him. Local workers refused to harvest his crops, and merchants and service providers avoided doing business with him. The local community effectively ostracised Boycott, isolating him socially and economically. This tactic proved so effective that boycott entered the English language as a verb in addition to its status as a noun. It also led to serious reforms that greatly increased the wellbeing of ordinary people not just in Ireland but in the entire British Isles as a more just land system was introduced.

In more recent history, and specifically pertaining to the property rights in question here, in 2011 Alexandra Elbakyan, a researcher from Kazakhstan established a website called SciHub. It has the explicit aim of refusing to recognise the property rights of the academic journals by enabling academics disillusioned with the system to use their access to the journals to share the articles on SciHub where anyone can read them for free. Unlike the 19th Century property rights revolt in Ireland, which received widespread societal buy-in, this innovation has divided opinion in the entire industry. Naturally, being the ones with the most to lose, publishers have responded aggressively. Elsevier won a lawsuit against SciHub in 2017 and succeeded in having its original domain shut down. Elbakyan was also ordered to pay damages. However, since she remains in her home country and runs the site through various aliases, enforcement of all aspects of the ruling is ineffective. The site continues to run through a series of mirror domains. Academics and librarians are more divided with younger academics with less to lose more likely to support SciHub. Librarians are also divided as although they would love to cancel their subscriptions, the prospect of academics using their access to illegally share articles with SciHub presents great risks to them. Everyone knows the system is corrupt but there is a lot of finger-pointing when it comes to solutions. Some academics demand that libraries cease subscribing to the journals now that SciHub exists (Others of course berate them when they can’t access an article). Librarians counter by saying it is academics that sustain the system by submitting to these journals instead of using preprint servers or journals that demand copyright over the material. They also argue, with evidence, that it is academia that primarily enables the impact factor to persist as it uses it as a primary measurement of academic achievement. If it weren’t important to academics it wouldn’t be important to libraries. So SciHub, although in widespread use and offering greater access to science, something that I certainly think is a good thing, isn’t changing how the system works. It’s not going to produce better, more reproducible science.

What are the lessons from these two historical examples? Sometimes civil disobedience over property rights is moral but collective action is hard. It only occurs when people become more motivated by what they can win rather than by what they can lose. In 19th Century Ireland, tenants were almost universally struggling to subsist. An horrific famine that took millions only a few decades previously was still fresh in people’s minds. Things were so bad they felt they had little to lose. Currently academics and librarians have a lot to lose. Their careers are on the line when they embrace alternatives, particularly ones like SciHub that involve law-breaking. On the other hand, ultimately, it is the government and not the industry participants that foots the bill and if they play the journals’ game, they can advance their careers. To suggest it’s far easier for academics and librarians to turn a blind eye to the system than it was for Irish tenants would be a massive understatement. Since this is a reality that won’t change, academia and universities are primarily publicly funded, only a solution that offers participants greater incentives than the legacy system is likely to work. Relying on moral arguments has thus far changed little.

What’s required is both a publishing system that offers greater rewards to academics and a curation system that offers greater rewards to librarians. If one existed, I’m confident the conversations these people would be having would suddenly sound very different. Many might think they had more to lose by not using it rather than not using the journals. We might finally see a boycott of the legacy system.