My last two posts painted quite a bleak picture of the present and future of institutional media. Yet, I ended with some optimism for the future of what I would call trustworthy information. That optimism is not merely an opinion, it’s something more tangible. I have gathered a team to build a platform that can fulfil the same role institutional media fulfils now, but is structured to thrive rather than survive in the internet economy. This project is called Olas and I will talk about it in this post.

Before I delve into what we’re building, let’s do a recap of the issues facing institutional media. Advertising revenues can no longer sustain much of the news industry and those that rely on them must degrade their product to survive. Subscription revenues only sustain a select few and lead platforms to publish solely for a certain demographic or narrative. Paywalls also reduce access to information, something which is of great detriment to society. The industry is becoming ever more concentrated. This is a bad thing. Government responses are only serving to increase this concentration, fossilising the industry, discouraging innovation and further empowering big tech by making media directly dependent on it. The incentives media faces, both from the advertising and subscription models, erode informational accuracy as platforms must optimise for clicks and subscribers ahead of anything else. Processes of editorial and peer review are often side-lined. Further, platform owners can, and do, set an agenda that is aligned with their economic and/or ideological interests, and often misaligned with truth-telling. Another issue I didn’t mention in the post is that many journalists – particularly investigative journalists – and scientists are criminally underpaid relative to the value they provide society. Economic precarity is only part of the explanation for this. Another major factor is that certain tier 1 media institutions and scientific journals enjoy entrenched positions that enable capital to extract more money than it otherwise could. These network rents are particularly bad in the case of media when you consider that the product is not just manufactured or delivered by journalists and scientists but created by them. Like the other ills of the industry, I consider this imbalance a market failure derived from the structure of our legacy media systems. Finally, aside from economic issues, media censorship is on the rise and trust in media is evaporating. Given that the problems are structural, it’s near impossible to see the situation improving unless we completely reimagine the institutional edifices via which we produce and consume information. This is what Decentralised Knowledge (DeKnow) and the Olas project aim to do.

Decentralised and Ownerless

The first institutional structures Olas is taking aim at are the actual institutions that publish information. Since forever, these institutions have, without exception, been proprietary – even if owned by the government – and hierarchically controlled. These hierarchies set agendas – whether by explicit direction from ownership or implicitly through groupthink and in the case of science, career focused networking – that are ever-present in groups of people. In our view, this is the main reason statistics show the accuracy of information found in news and science media publications is sorely lacking. It is also one of the main reasons trust in these institutions is in freefall as people are increasingly aware they are being manipulated. Finally, it’s why people like Rubert Murdoch and Michael Bloomberg, and institutions like the US local news publishing giant Gannett, continue to amass enormous profits while journalism becomes an increasingly unattractive career.

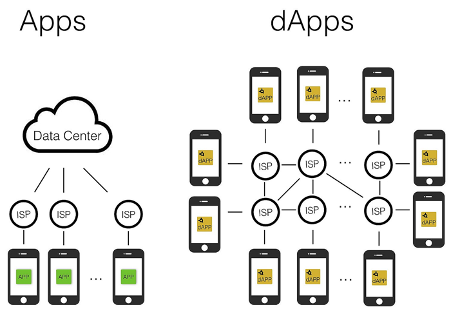

We believe accuracy won’t improve, trust in media won’t be restored and journalism won’t become a fairly rewarded profession again unless hierarchies are removed and a media platform that is neutral by design is implemented. That is the primary goal we set ourselves at Olas. Throughout history, such a goal was impossible as institutions have always required hierarchies to avoid a ‘tyranny of structurelessness’. However, thanks to recent technological advances, it is now achievable. Several years ago, the invention of a new form of distributed ledger technology, known as blockchain technology, that is secured by distributed entities following economic incentives rather than human hierarchies and regulation, revolutionised how people think about internet applications. Once code is published on one of these ledgers, it cannot be tampered with by anyone, including its creator(s). The application simply persists as designed on this extremely secure distributed infrastructure. Although this comes with a lot of risk – all the code must be perfect and execute as its creator intended – the enormous benefit is that internet applications without owners that set agendas and extract huge rents are now entirely possible. These decentralised internet applications (dApps) more resemble the open internet protocols that proprietary internet apps are built on today.

The only thing that stands between those who supply a product using these protocols and those who consume it is computer code. The power lies in the code, and nobody wields it. The applications work without hierarchies. I believe it’s hard to overstate how much of a breakthrough this is for humanity. Most of the power and money amassed by entrenched internet giants from their huge network effect advantages, can now be dispersed to users. Further, without any central point of control, authoritarian regimes cannot compel these applications to do their bidding. It’s a massive leap forward for both individual human freedom and economic growth.

Olas will be one such decentralised protocol in the information realm. A news media platform without a media mogul. A media platform Vladimir Putin or Xi Jinping can’t interfere with. A media platform where the vast majority of the fruits of a journalist’s, fact checker’s, or reviewer’s labour, flow to them alone. A media platform where scientists profit from their publications instead of the owners of academic journals reaping all the profits from publishing publicly funded scientific research. A media platform where users and communities, following much healthier economic incentives than exist in the current system, police themselves to halt the spread of misinformation and increase the replicability of scientific output rather than there being Orwellian gatekeepers of the truth. Above all, a media platform people can trust, that doesn’t have an agenda, because it can’t have an agenda.

A New Economic Model

The second institutional structures we’re taking aim at are the advertising and subscription models that dominate the industry. At Olas, the challenge we set ourselves was to design a system where information is freely accessible to everyone – because nothing advances humanity more – yet not only amply rewards content creators, but does so in a way that minimises the negative impacts of money on the quality of information produced. The latter requires completely new systems of quality control that introduce healthier incentives into the system. I will leave discussion of those systems to another section. Here I will describe how content contributors on Olas will access funding in the first place.

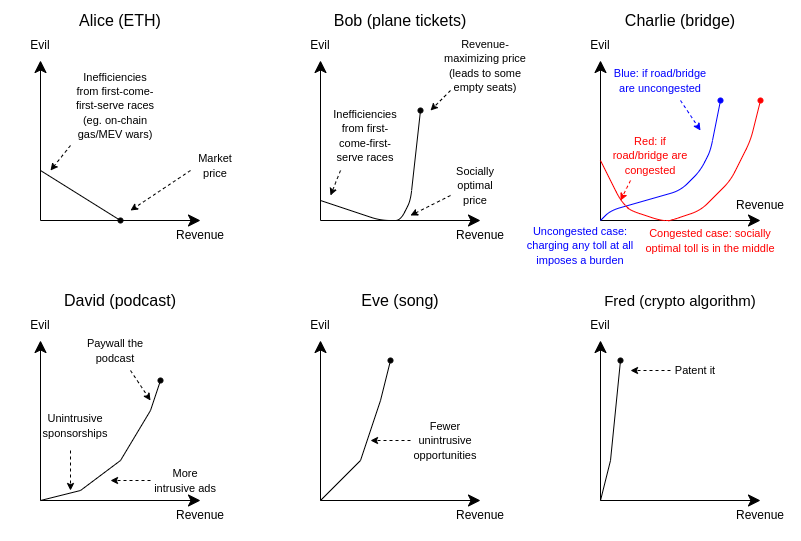

Many economically minded people will read the challenge we set ourselves and immediately conclude that any solution to this challenge is utopian and bound to fail. How on earth can one make a product freely available and expect to compete with institutions that don’t? One could rightly point to the history of underfunding for open-source software versus the enormous profits earned by proprietary internet applications that cornered their respective markets. However, information, particularly in the digital age, holds properties that suggest treating it as a private good is actually not a long-term winning strategy. Although new information can be costly to discover, once it is discovered, it propagates easily and is difficult to suppress, almost impossibly so on the open internet. This is of course why copyright rules exist, rules that are themselves highly imperfect in terms of positive outcomes for society. Since these properties mean information is a natural public good, unlike the case of natural private goods, generally attaching private business models to information tends to cause degradation of its quality. The theory behind this is outlined in this ingenious rethink of how we view public goods provision by Vitalik Buterin.

In practice, we can see many of the so-called free-to-use websites that rely on advertising becoming steadily worse over time – a phenomenon that led to the coining of the phrase “the enshittification of the internet” – as their owners are constantly optimising for the things that make them money, rather than their core product. The great enshittening, in my view, not only includes the demise of user experiences on social media platforms, or Amazon, or Uber, but includes the rise of clickbait news and the highly inefficient subscription model which forces consumers to buy bundles of articles, most of which they don’t want. Turned off by a user experience polluted with ads and overwhelmed by subscriptions, consumers are voting with their feet. This means that platforms that publish some information consumers would pay for, are folding. Here we have one of those rare cases where private business models are, in fact, making the market smaller than its potential.

So therein lies not just the opportunity for us to achieve our ideological goals of making all non-private information free to all, but an enormous market opportunity for a platform based on an economic model more suited to public goods. This begs the question, what economic models are suited to public goods? The answer is that there is only really one: Subsidies. When these subsidies are provided by the government, we tend to call the product public services. When provided by the private sector, we tend to call it charity or tipping. Of course, charity is already an enormous market. It’s difficult to measure but it’s almost certainly worth over $1tn annually. NGOs, one part of the market that is measurable, account for ~$500bn of that. Tipping, particularly in restaurants, is commonplace in much of the world. Several media platforms, such as Wikipedia and The Guardian already subsist on donations. So in many ways it shouldn’t be that controversial that this would be a viable model. However, if it had such clear advantages currently, it wouldn’t occupy a niche but rather it would be in widespread use across media.

There are two reasons why it’s currently not a competitive model. Firstly, micropayments made using payment processors aren’t economical. Consequently, donations are requested in monthly subscription-sized amounts rather than on a per-article basis, which is by far the most efficient way of matching supply with demand. Secondly, the user experience of payments involving centralised payment processors on the internet is still far from seamless. The effort involved can be a deterrent even for payments one needs to make, let alone discretionary ones. Consumer subsidies won’t be a competitive model until this situation changes.

The good news is this is changing. Another huge benefit of the impending decentralised web, or web 3.0 as it is often called, is that micropayments will be economical and as trivial to execute as liking a post on social media is today. Moreover, there is no requirement to sign up to the dApp within which you are making a payment, let alone receive an email confirmation. There’s no need to add credit card details. There’ll be no security check for such small payments. The entire process will be as close to frictionless and as ‘cash-like’ as possible on the internet. These are the benefits of payments without intermediaries, something this technology, being decentralised, offers by default. Since the Olas Foundation is building software that will live on some of these Web 3 platforms, it will benefit from and be interoperable with this payments infrastructure. With payment frictions removed, Olas can help journalists and scientists fully exploit the enormous untapped potential in media markets that advertising and subscription models cannot service. It will provide a platform for journalists to raise money in advance of doing any work so that they will have a certain amount of predictability in their earnings, as well as having the ability to receive tips post-publication. To minimise the effect of big money interests, ensure a plurality of voices, and ensure communities rather than bureaucracies have the greatest say in who gets funding, Olas will employ a novel fundraising mechanism called quadratic funding. I will not expand on this concept now as it requires its own post to fully explain, but I will dedicate one to it soon. The payouts in tips for some markets, notably investigative journalism and science, may be so great that investment would be a viable model in these sectors. This would be fantastic as the upfront costs in those areas can be substantial. That too is something that will need a separate post to develop.

Community Quality Control

Since, by design, Olas dispenses with human hierarchies administering the platform, by default, it cannot have hierarchical review processes. However, if we don’t institute review protocols, we would simply have recreated social media in a decentralised setting, something that is certainly not a solution to the problem we’re trying to solve. Consequently, we are left with no choice but to reimagine the institutions of editorial and peer review too. Reforming these institutions is a choice we would gladly take in any event as our legacy systems of editorial and particularly peer review are clearly not fit for purpose.

In a distributed setting with no hierarchical credential-based systems, there are only really two tools available to us to improve the quality of information: Markets and reputation. The good news is that these are probably the most powerful tools humanity has at its disposal for learning and improvement when well designed, because being wrong, performing badly, and earning a bad reputation, is costly. In the context of what we’re building, there is already quite a large body of evidence that shows prediction markets perform much better than peer review in science. However, outside of sports and politics, prediction betting markets haven’t ever really taken off. Some of the explanation for this is regulatory, but I believe there is another major reason too. That major reason is that outside of those two areas, there aren’t enough passionate or fanatic bettors that bet with their hearts rather than their heads, and thus, provide a subsidy to shrewder market participants that can enter to make a profit. It is these participants that make the market efficient.

Despite their enormous benefits, markets and reputation systems are vulnerable to being manipulated. We know in market situations, those with large amounts of money can often move the market in the direction they wish it to go in. This strategy can be intentionally loss-making to accrue larger gains elsewhere. Consequently, the market in question gives poor quality information to participants. In market-speak, prices would not reflect fundamentals. Supermarkets sell many products at a loss to attract customers into the building and buy other products they enjoy a much larger margin on. This is unfair to producers of those products if it translates into lower prices for them. The government of Saudi Arabia is currently spending enormous sums in the sports industry, in one instance setting up a rival tournament (LIV) to the US and European golf tours and attracting players by offering enormous sums of money that are not in any way reflective of the earnings of the new tour. Given the economics, many claim the regime is simply using their sovereign wealth funds as marketing expenditure. This of course would mean LIV is a ‘loss leading’ product for the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Only time will tell if LIV will eventually be run economically. If we were to be charitable, it is the only market strategy available to the Saudis. Given how entrenched the other two market participants are, the only way a newcomer can gain a foothold is to operate with deep losses for some time. This is a related flaw of markets. Due to the effects of market power, they trend towards a low-competition environment, a trend which is occurring in media too. Markets perform exponentially better with power dispersed among many competitors.

Reputation systems are also vulnerable to being manipulated. It is trivially easy to establish many identities online and use those identities to obtain multiple votes from the same person. It is also easy for groups of people to collude to agree to give a certain product, service, or identity a certain review score. On many platforms, the identities aren’t even human, but bots built specifically to manipulate outcomes. These flaws mean that things like Tripadvisor restaurant reviews and Amazon product reviews, while useful, are nowhere near as informative as they could be.

At Olas, we understand very well that, given our goals, we must rely on these tools to provide high quality information. We also understand both their general flaws and the reasons why prediction markets, despite their enormous promise, have yet to catch on in this area. As a result, we have designed our market mechanisms with this information in mind. To ensure a prediction market system is economically viable, we extend the subsidy model to Olas users who participate in review markets. Bettors in review markets are paid to bet. We have also gone to great lengths to ensure the design is highly resistant to being bought or manipulated by humans gaming the identity layer. This means that the identity layer is resistant to both bots and people establishing multiple identities (Sybil attacks) using novel proof-of-unique human protocols. The effects of big money and collusion are minimised by randomly selecting review protocol participants.

What does this mean in practice? To use the case study of news reporting, after a writer has raised money, they must write articles to gain access to the funds they have raised. Each article published is accompanied by a stake. A certain percentage, let’s say 20% for now, of that stake is put aside as a bounty for fact and context checkers to discover faults with the article. If a reader finds an issue, they can register a claim for a share of the bounty. Once this happens, after a certain period, a judging panel is established to adjudicate between the writer and the checkers. Half of the panel will consist of writers who have stated expertise in the topic in question. They will have funds locked in the protocol as they would have previously raised money to write on the topic in question. When they are selected for judging duty, they are forced to use some of these raised funds to bet on the merits of the relative claims. This is part of the social contract of Olas. If you raise money to write, you’re also expected to commit some of those funds to participate in review markets of topics you claim to have knowledge of. The implementation of this rule ensures review markets are always subsidised.

To prevent subject matter expert groupthink, some seats are left open to other people who believe they have insight. They too must stake money on that insight. The overall score given by the panel dictates the pay-outs to writers and fact checkers while the relative scores of panellists to each other dictates the pay-outs to individual panellists. Reputation scores are updated according to the participant’s performance in the market, giving future funding market participants valuable information about who is most deserving of funding. The identities and votes/bets of each panellist are anonymised. Further, no two judging panels will be the same as identities are prevented from sitting on the same panels together regularly. Consequently, the system is highly resistant to collusion and concentration of power, with any hierarchies formed to review information being random and temporary. The only viable profitable strategy for a participant is to bet on what one genuinely believes to be true. Unprofitable strategies aren’t sustainable as anyone that attempts to follow one will see their reputation ruined and their voice severely diminished. Those who earn the most using the protocol will simply be those who perform the best. Credentials and networks will not affect outcomes so nobody will be able to hide behind them. Opinion markets and scientific research markets come with their own unique challenges which we have also designed specific market mechanisms to meet. All the market mechanisms can be reviewed in the documentation section on the Olas website.

Conclusion

This post laid out a path forward for an open media protocol free from the control of powerful interests, with native mechanisms for funding quality information as well as native crowd-based quality control mechanisms based on healthy incentives. Given the technologies that are coming available to us, we believe it is possible to radically transform media for the better. When all three of these foundational blocks are in place, we can start to see all sorts of other benefits. Those that inhabit comment sections of news platforms gain a new income stream from providing insight, if and only if, it is valuable. Since judging panels will also check the originality of the content, our system can become a much cheaper form of plagiarism protection than copyright laws. Sure one can copy and paste the information onto another platform but will anybody trust it without proof it’s gone through quality controls? With the advent of AI, and its ability to flood the internet with information, I believe people will demand to see an Olas quality control stamp on the information they consume. And since a writer’s content on Olas must be original to receive a good score, original content is protected from theft by default. From a reader’s point of view, as articles are freely accessible, people will be able to build their own newspapers, featuring journalists and topics they’re interested in, from an enormous open database without having to move between platforms. If others find their curation valuable, they too can receive tips for this with most value still flowing to those that created the content. These are just some of the many benefits that come from Olas makes possible.